Author: Ethan Perry

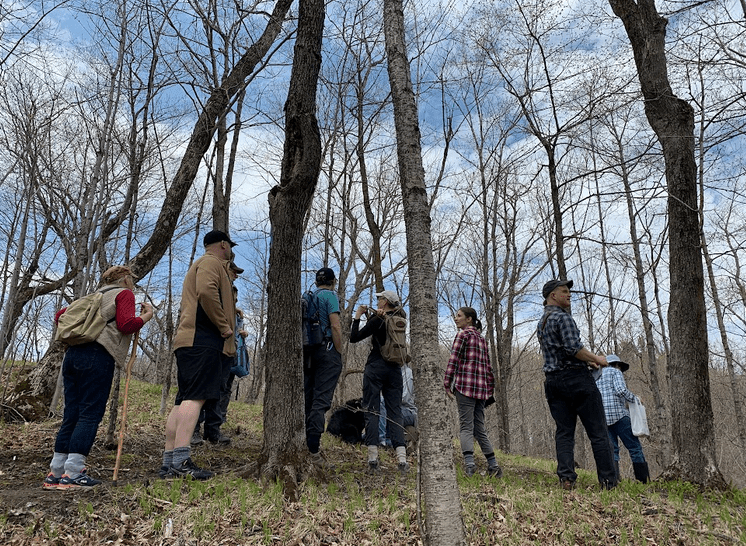

On Saturday May 11 we gathered for our third annual spring wildflower walk. This year we tried a new location: a short stretch of the Superior Hiking Trail in far western Duluth. We also adjusted the date because unusually warm weather in early spring when the date was set suggested the flowers could come early. As it turned out, cooler weather slowed everything down, and the wildflower peak is yet to come. But catching the earliest blossoms on a gorgeous sunny day was a fabulous kick-off for the season.

We started at the Snively ski trail parking lot, where president Kelly Beaster introduced us to some history of the Magney-Snively Natural Area, established in 2006. Although the area is now named after two former Duluth mayors, it’s part of a ridge called Manitouahgebik (Spirit Mountain) in Ojibwemowin and has great cultural and religious significance to Ojibwe and Dakota. It also overlooks Manidoo-minis island in the St. Louis River, the prophesied sixth stopping place of the Anishinaabeg migration story. The Natural Area was established to protect 1800 acres of an even larger expanse of forests, creeks, and rock outcrops at the western end of Duluth. It contains high-quality examples of two types of hardwood forest, one near the northern edge of its range and one at the southern edge.

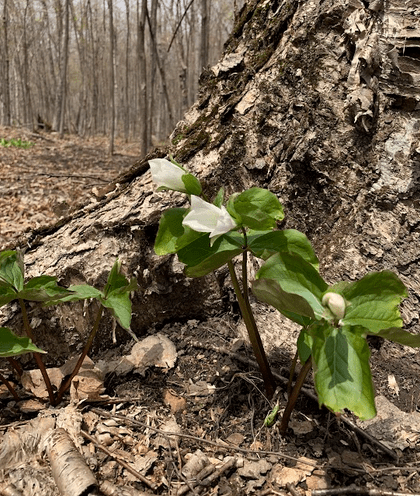

When we embarked up the trail, we quickly saw large-flowered trillium (Trillium grandiflora), mostly still in bud, but a few already open. Some hepatica (Hepatica americana), which bloom even earlier, still showed their tiny lavender petals. We stopped along the trail to talk about the four patches of old-growth forest in the Natural Area, defined as having some trees over 120 years old. When some of the old-growth was slated to become a golf course in the early 2000s, the effort to protect the forest resulted in the creation of the Duluth Natural Area Program, with Magney-Snively its first inductee. As we stood there, we also began to talk about one of the small understory trees around us: ironwood (Ostrya virginiana). As always happens on our walks, we all shared our knowledge, including the use of ironwood for the frames of waaginogaan lodges.

As we continued, we were lucky to see a couple patches of bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) still flowering and cutleaf toothwort (Cardamine concatenata), as well as the very first bellworts of the year, both large-flowered (Uvularia grandiflora) and sessile-leaved (U. sessilifolia). When we reached a few Dutchman’s breeches plants (Dicentra cucullaria), with tiny white pantaloons thrust above their finely-dissected leaves, it was time to call it a success and head back to the cars.