Written by Ethan Perry

What could be better for a bunch of native plant enthusiasts to do on a November night than gather to hear about another excited place to explore? For our last event, at Hartley Nature Center, that exciting place was the newly established Icelandite Coastal Fen state Scientific and Natural Area (SNA), about 11 miles beyond Grand Marais. ANPE’s own Kelly Beaster and Sarah Beaster told us everything we’d want to know about it before going to experience it ourselves.

First, the name. It comes only indirectly from the island nation in the north Atlantic. The SNA is named for a type of volcanic rock that was first described in Iceland. Minnesota’s bit of Icelandite was discovered in the 1960s by John Green, a UMD geologist who was mapping the types of bedrock along the shore of Lake Superior

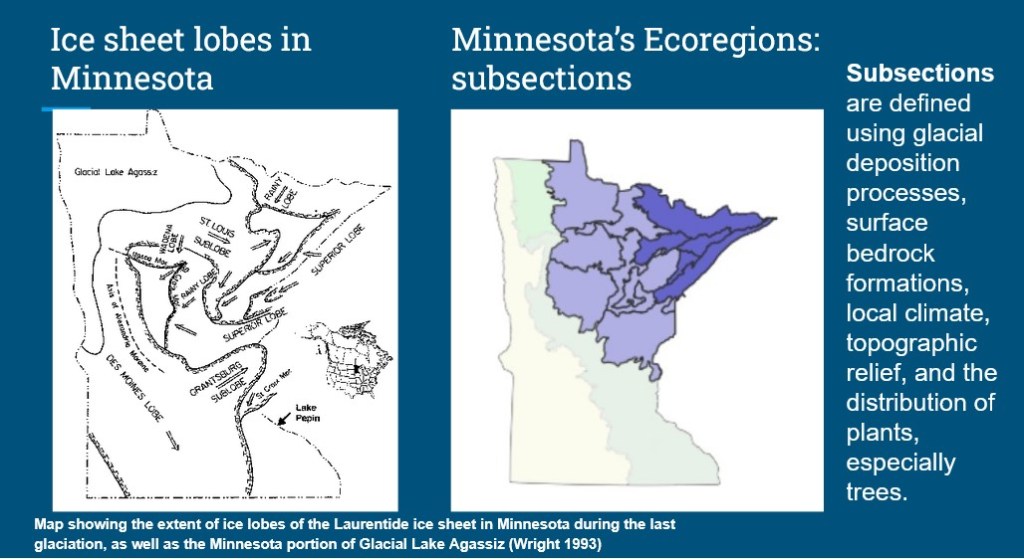

As Sarah and Kelly explained it, all the bedrock on the north shore was produced by lava flows millions of years ago when a great rift valley opened across what’s now the Great Lakes region. Most is basalt, with lesser amounts of rhyolite. Icelandite is somewhat intermediate between the two. It underlies the western portion of the SNA, and it is most easily seen at a rock cut along the highway to the west.

Decades after the discovery, John Green nominated several sites to the SNA program to protect unique geological and biological features in the region. Two others, Sugarloaf Cove and Iona’s Beach, were established years ago. After many complex negotiations, Icelandite was purchased from the Minnesota Dept. of Transportation in 2021 and formally dedicated just this summer.

The Minnesota SNA program, part of the Dept. of Natural Resources, exists to protect places with populations of rare species, the highest quality remnants of native plant communities, and/or unique geological features. Icelandite is unusual among SNAs in having all three components. The high quality native plant community there is the coastal fen that also contributes to the SNA name.

“Fen” is the name for a type of wetland that occurs throughout Minnesota, but is more common in the north. Unlike the strongly fluctuating water levels of wet meadows, fens are constantly saturated, allowing for the accumulation of peat. Unlike bogs, another type of peatland, fens are influenced by groundwater, which provides some nutrients that bogs lack. The sloping bedrock shore of Lake Superior allows for little wetland development, and according to Kelly and Sarah, only two of Minnesota’s shoreline wetlands are fens. One, at Sugarloaf Cove SNA, was destroyed long ago. Icelandite has the last one.

Sarah and Kelly shared photos of some of the plants that inhabit the fen, including dragon’s mouth orchid (Arethusa bulbosa) and a sedge by the name of Trichophorum alpinum that looks like a miniature cottongrass. Also found is shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), which is common in large western fend, but also shows up on the rocky shoreline of Lake Superior. Kelly said of all the coastal wetlands she had surveyed, no others have shrubby cinquefoil.

If you’d like to see Icelandite for yourself, the Superior Hiking Trail takes a dip down to the lakeshore there and runs along the gravelly beach. From the crest of the beach you can look back across this unique wetland, and when the fen is frozen you can poke around without damaging the sensitive plants.

To learn more about SNA’s in Minnesota, visit the DNR Scientific and Natural Areas webpage.