Written by Ethan Perry

Walking the Waabizheshikana trail in western Duluth as the threat of rain faded, we had a view across the open water of Kingsbury Bay. Patches of manoomin (wild rice, Zizania palustris) ringed the edges. Reed Schwarting, who led our session on aquatic plant identification, explained that only 10 years ago this bay looked completely different. Instead of open water with submerged aquatic plants, we would have seen a solid expanse of hybrid cattail growing on deep deposits of excess sediment carried in by Kingsbury Creek.

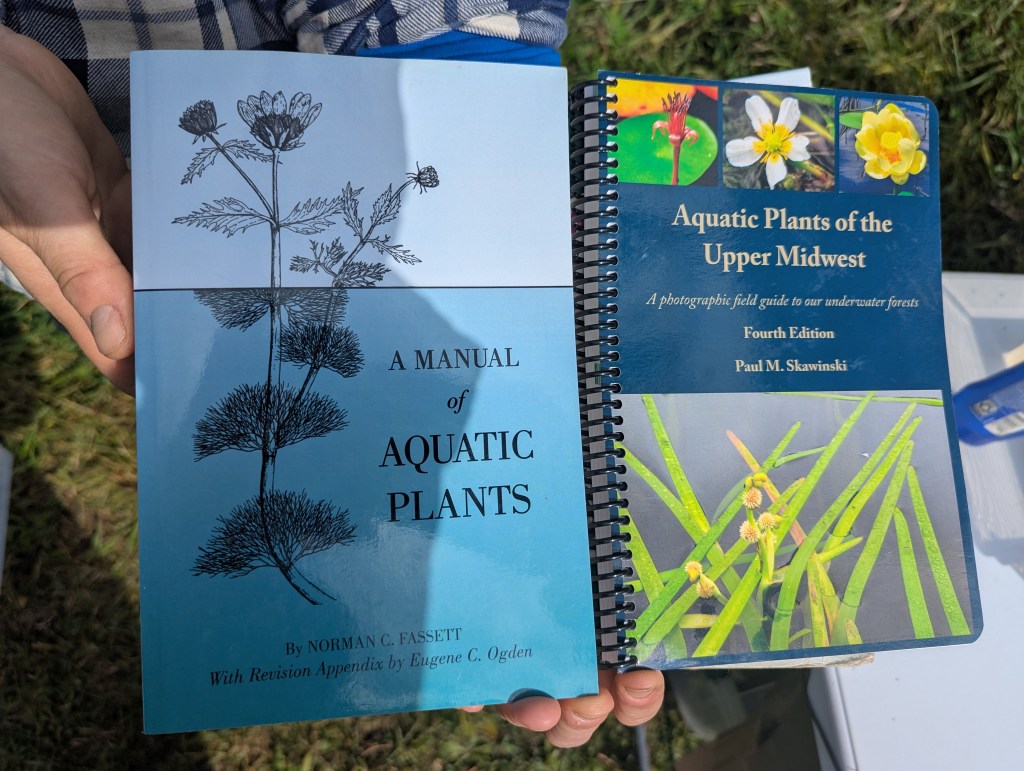

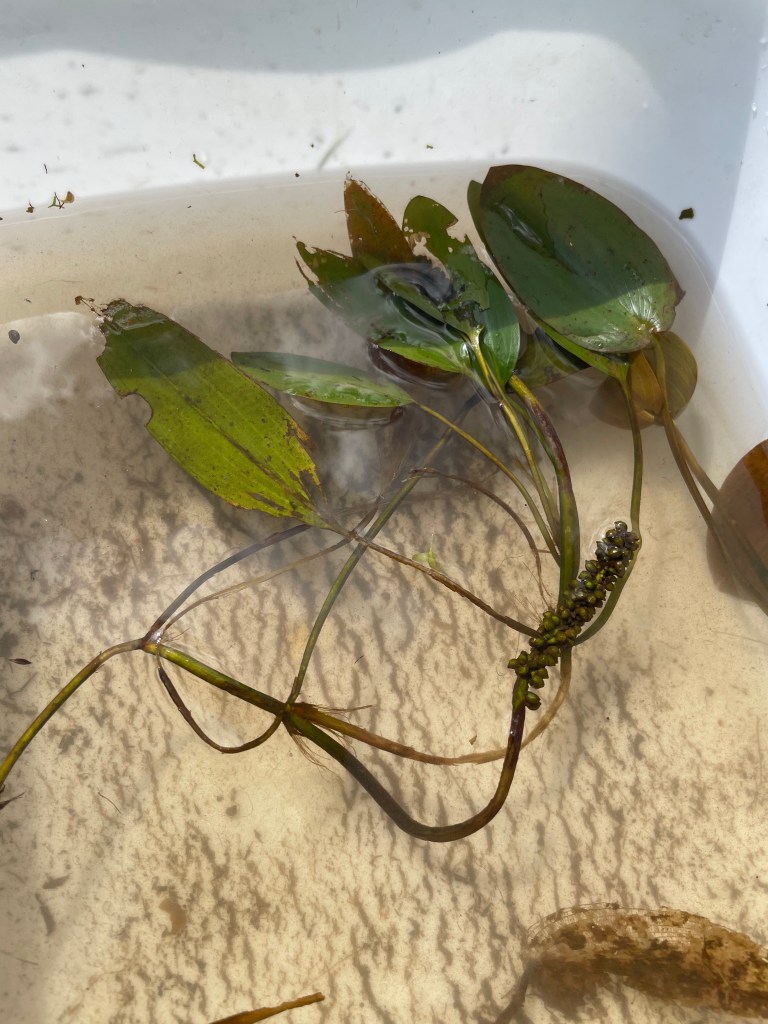

Reed, a botanical researcher at the UWS Lake Superior Research Institute, set up two plant identification stations for us, one at our meeting spot at the Kingsbury Creek Restoration kiosk and another overlooking the bay. At each station were numerous examples of plants Reed had collected for us, including tubs of water for submerged species so we could see their aquatic growth forms. He also had field guides with illustrations, and he even donated a copy of Skawinski’s Manual of Aquatic Plants to ANPE’s lending library.

Reed divided aquatic plants into three categories based on water depth: wetland, emergent, and submerged. At the first station we began with a variety of wetland and emergent species, and we were able to handle all of them for a close look. One familiar emergent is cattail (apakweyashkway, Typha spp.). There is a native broadleaf cattail (Typha latifolia) in Minnesota, but the most abundant type (Typha glauca) is a hybrid with a non-native species. The hybrid can take over large areas that have experienced some disturbance.

On the short walk to the second station Reed described the restoration of the bay, which involved excavating large amounts of sediment, along with most of the hybrid cattails. Afterward, in the now deeper water, manoomin was re-introduced to the habitat where its abundance once sustained Dakota and Ojibwe villages both nutritionally and spiritually before industrial development eradicated it. On the north side of the bay the rice is well-established and expanding out from the shoreline. On the south side there are still fenced exclosures to protect it from foraging geese while the bed gets established.

Manoomin typically grows in a zone between shallower emergents and deeper submergents. At our second station Reed showed us a diversity of aquatic plants that grow in water too deep for emergents like cattail. Among them are three species of water lilies (Nymphaea odorata and Nuphar spp.), pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.), northern watermilfoil (Myriophyllum sibiricum), the non-native Eurasian watermilfoil (M. spicatum), and eelgrass or water celery (Vallisneria americana), which Reed says is the most abundant aquatic in the Chigami-ziibing (St. Louis River) estuary. Even though these aquatic plants mostly grow beneath the water, almost all of them send stems above the surface for flowering, and some have floating leaves. Many, like eelgrass, provide important food for migrating waterfowl.

We can all go back to Kingsbury Bay and watch these species recover over time and perhaps help remove non-natives that could threaten to take over again.