Written by: Kelly Beaster

This November, ANPE members took a deep dive into one of Minnesota’s most elusive conifers – eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) or Gaagaamich in ojibwe, meaning ‘porcupine tree’. Ethan Perry, botanist and plant ecologist with the MN Department of Natural Resources, shared some unique characteristics of hemlock, including that it superficially can resemble balsam fir (Abies balsamea) but upon closer examination (which members were able to do with samples cut that day) one can see the shorter, slightly tapered needles of hemlock compared with the thinner, longer and more sparsely spaced needles of balsam fir. The bark of a mature hemlock has deep furrows and resembles the bark of a mature white pine.

Hemlock are incredibly shade tolerant and long-lived. A hemlock can survive at seedling/sapling size receiving as little as 5 percent sunlight coming through the canopy to reach that individual for well over 100 years, waiting for a canopy gap to occur where the hemlock will increase growth. The oldest living hemlock in Canada is 532 years old, meanwhile in the eastern US, hemlock were commonly aged between 400-600 years old. It is believed that hemlock can live over 800 years.

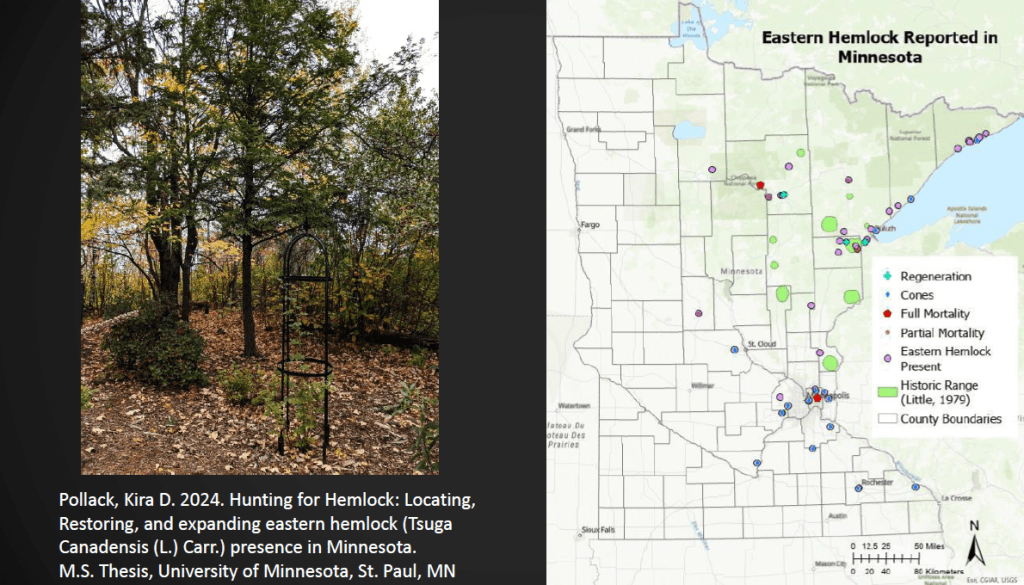

Hemlock are incredibly susceptible to deer browse, as Ethan stated, “They are like candy” to deer. A deer browse study was done in the eastern US with some caged and some not caged hemlock. Those that were caged saw a 60% survival rate and it took them 33 years to reach maturity when the fences could be removed. Meanwhile, those that were not caged saw only a 15% survival and it took those seedlings 78 years to reach maturity and grow above the browse line. This is significant for hemlock in Minnesota because white tailed deer were never in our northern forests until the era of logging and will suppress any natural regeneration without protection.

But perhaps another draw to this unique conifer is the mystery of how it got to Minnesota. Did it migrate here, and if so, why didn’t those populations expand? Was it brought here by humans, and if so, what could those populations be representing? And, how will it survive in Minnesota into the future with a changing climate and the adelgig pest that is devastating hemlock forests out east but isn’t here yet?

To answer the story of how hemlock arrived, Ethan shared several studies, one about pollen and the other about genetics. Studying the pollen record, Randy Kolka discovered that our hemlocks showed up 2000 years ago at approximately the same time hemlock had advanced to their most westerly population in Wisconsin. Hemlock populations have been pretty stable since then, not expanding as one would have guessed. Ethan has been relocating historical observations of hemlock across Minnesota to confirm their presence. Some of those populations he has been unable to relocate, or we know they have been wiped out due to historical events, such as the 5,000 hemlock that were burned in the 1918 fire.

At the same time, the genetics of hemlock in Minnesota have been coded and the results are intriguing. Hemlock appears to have been a popular conifer and planting plans exist for places like Glensheen, so we know those hemlocks are not of natural Minnesota origin. The hemlock in Hemlock Ravine SNA, however, show unique genetics to any other hemlock in the state, suggesting they were an isolated population that has interbred for long enough to veer from the original genetics. Those in west Duluth share similar genetics to Wisconsin hemlock, suggesting they migrated from Wisconsin or were planted at some point with Wisconsin stock. Taking into account the genetics, historical accounts of hemlock populations and some observational evidence like whether a specimen was found on a private estate or within a forested region, Ethan has mapped 30 hemlock in the entire state that are assumed to be of natural origin.

Ethan shared a couple of recent confirmations, including one north of Duluth that was spared from logging around 2000. It still stands and is likely 210 years old and has grown 3” in diameter over the last 25 years. Another recent find was a 1974 record of a hemlock northeast of Duluth. Ethan confirmed its existence this year, and the proud caretaker of this individual was in the audience and shared that there were a couple of seedlings nearby that had been caged. Ethan invited members in attendance to share their hemlock stories, and as inevitably happens with hemlock, there was a lot to tell.

Knowing that so few mature individuals still survive in Minnesota and that natural regeneration is unlikely without human intervention, the DNR is considering a hemlock recovery plan. This would have to take into account the natural genetic variation and if hemlock seedlings are planted and protected, which parent trees should the seed come from? One thing is certain, without human help, hemlock grow too slowly and are too favored by deer to spread quickly enough to migrate to the newly suitable habitat created by the changing climate.

If you missed the talk, you can view the Hemlock Slides Here.