Written by: Ethan Perry

ANPE treasurer Rubin Stenseng gave a warm presentation on Minnesota orchids on a cold night, Tuesday January 21, 2025 at Hartley Nature Center. He began by asking what orchids bring to mind for us, and he listed words he has heard in the past. A feeling of “mystique” is common. Given some of the topics Rubin discussed later, perhaps the best word came from a member of the audience: “trickster.” No doubt the complex blossoms of some orchids attract us.

There are approximately 28,000 species of orchids worldwide, among the largest plant families. Many are tropical epiphytes growing on tree branches, and some make good houseplants. Rubin emphasized the importance of purchasing propagated orchids rather than those collected from the wild. Orchid thieves have decimated some populations, and Rubin himself has observed holes in the ground where Minnesota orchids used to grow. Be careful with social media or iNaturalist posts that may reveal precise locations to people with harmful intentions.

There are 46 orchid species in Minnesota, with 3 of those having 2 varieties. Ten are listed as endangered, threatened, or special concern. The comprehensive reference for Minnesota orchids was written by state botanist Welby Smith, but for a field guide Rubin recommended Kim and Cindy Risen’s Orchids of the Northwoods.

Minnesota orchids range in height from just a few inches up to 4 feet tall, in flower size from tiny to large and showy, and in color from green to yellow to pink. All orchid flowers have 3 sepals and 3 petals, one of which is modified into all sorts of odd shapes and is called a “lip.” Some lip petals have a long spur with nectar to attract butterflies or moths. Many of the tiniest orchids with miniscule flowers also produce nectar for the purpose of attracting pollinating mosquitoes.

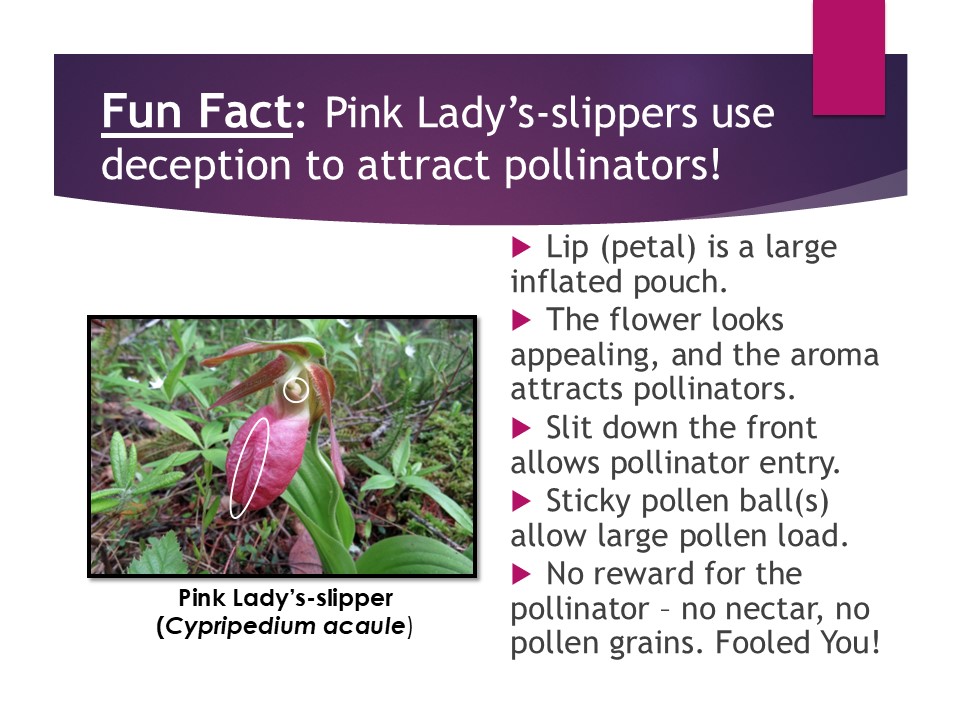

Rubin described many Minnesota orchids, beginning with the most common, the pink lady- slipper (Cypripedium acaule). This species, like many orchids, does not offer pollinators any nectar or pollen, but tricks them into pollination. The lip of lady-slippers is an inflated pouch that attracts queen bumblebees with its color and draws them inside with its scent, but they find nothing to collect. The only exit at the top of the pouch forces the frustrated bees to brush against sticky pollen balls, which they carry to the next “trickster” flower.

Another group of orchids Rubin highlighted was the rattlesnake plantains (Goodyera). The downy rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera pubescens) is especially notable, considering ANPE president Kelly Beaster’s illustration of its striking network of white veins serves as our logo. It’s rare in the Arrowhead, and Rubin has the distinction of recording the only recent occurrence in St. Louis County.

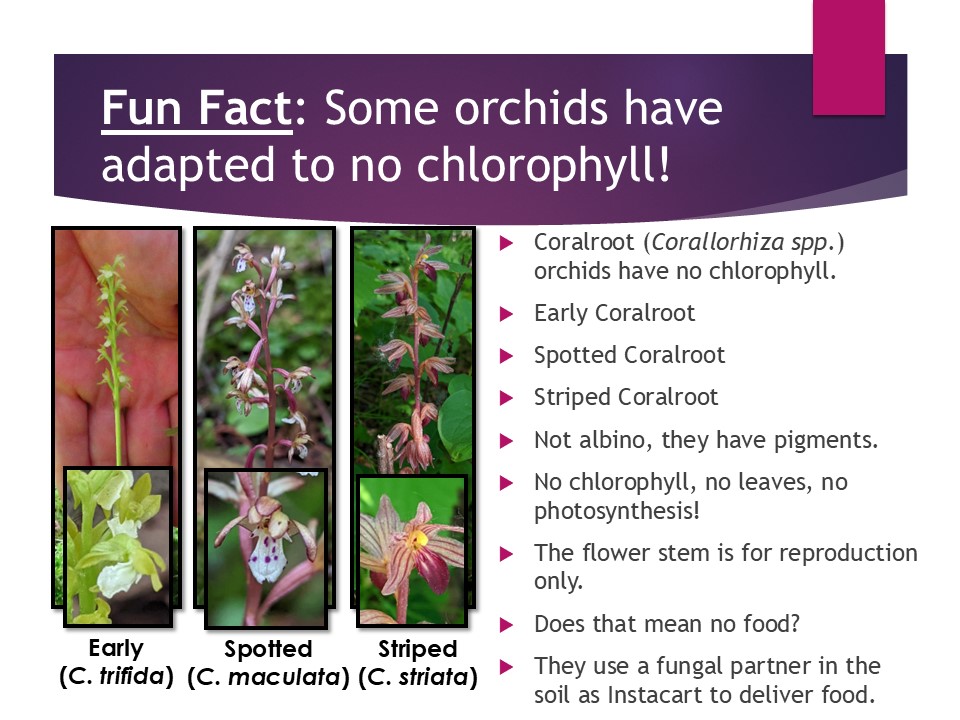

All orchids require a fungal partner living in the soil. In fact, their dust-like seeds carried on the wind can’t even germinate until the right fungus breaks in and supplies nutrients. As they grow, an active trade develops, with sugars from the orchids exchanged for the nutrients. Coral roots (Corallhoriza) are Minnesota orchids that have no chlorophyll and cannot photosynthesize to produce sugars. What the fungus receives from them in return for nutrients is unknown, or

perhaps it’s a parasitic relationship. Digging up orchids often results in the death of the fungus, and ultimately the orchid too.

Rubin went on to describe a variety of other Minnesota orchid species, as well as the history of mistakes concerning the designation of our state flower, but to hear about all that you’ll have to catch one of his future orchid presentations. And if orchids have you really hooked, be sure to check out the orchid group that Rubin plans to start within ANPE this spring. They will be driving far and heading off-trail into the swamps in search of Arrowhead orchids.